Introduction

Introduction

Our world exists in time, in a history that does not just stretch into the past but unfolds constantly, with ever more surprises. A century ago, you could hardly find a subject more abstruse or forgotten than the esoteric tradition known as Kabbalah. Only a tiny handful of people had ever heard of it, let alone studied it or tried to bring its wisdom into their own lives. To many of those who did know of it, it seemed overly complicated and medieval, hardly suitable for the new, modern, twentieth century.

Kabbalah is a Jewish mystical tradition, with ideas first developed two thousand years ago, and most elaborated from the twelfth century onwards. The Hebrew word Kabbalah means “received,” as an oral teaching is received by a student directly from a teacher, or perhaps in revelation, directly from God. And yet it was not primarily Jews who kept the tradition alive a hundred years ago, it was a small group of occultists, Christians with great interest in Pagan as well as Jewish traditions. Their main influence outside secret initiatory groups seemed to be among artists and writers seeking an underpinning of meaning to their creative impulses. Growing up in an Orthodox Jewish home in the 1950s I did not even hear the word Kabbalah until, as an adult, I discovered Tarot cards and began to learn their spiritual and interpretive tradition.

And now, as we begin the twenty-first century, this mysterious, ancient teaching has sprung up everywhere. Movie stars go on talk shows to proudly proclaim that Kabbalah has changed their lives. Books appear telling us how to use Kabbalah to have good marriages and successful careers. Kabbalah’s most famous symbol, a diagram known as the Tree of Life (in Hebrew aytz chayim) now shows up on greeting cards and silver necklaces. Such are the wonders of history.

This book concerns that symbol, that marvelous tree. In particular, it explores a special version of that symbol, a lush painting by Hermann Haindl, a man who has dedicated his life to art as a spiritual path. Haindl is probably best known for the Tarot cards he painted some twenty years ago. Brilliant and complex and filled with meaning, they became one of the most popular Tarots of recent decades.

Even then, Haindl was interested in Kabbalah, for he painted a Hebrew letter on each card, a tradition that goes back to those occultists more than a hundred years ago (see chapter two, on the history of the tree). Now he has given new life to the tree image, with some of the same themes he developed in the cards—the sacredness of the earth; the power of very old images; the holy wisdom of indigenous peoples, especially from Native America; the way nothing in nature ever stays the same but over time transforms, one thing into another, animals and trees into stone, stone into life.

The tree symbol comes from a tradition that bases itself on ecstatic awareness of the divine. At its heart its power is not intellectual but revelatory. And yet so many teachers have pondered it, and written about it in such complex ways, we can all too easily let it become a purely abstract study of ideas, with long lists of attributes the student tries to memorize. The tree itself can appear a sort of geometric diagram rather than a living image. What Hermann Haindl has done is make this ancient symbol fully a Tree of Life. His painting teems with life, like some magnificent rain forest of the mind. We see birds, and snakes, and animals, and faces. We can make out ancient mythological beings, and Jesus, and faces made of eroded stone. His tree is no less mystical for giving us such richness of life. Instead, he reminds us that all knowledge of the divine begins in nature—nature and the human mind as it looks with wonder at the glory of existence.

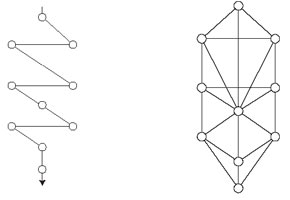

In its common form, the tree symbol looks like this.

These ten circles represent ten pulses, or emanations, of divine energy, called in Hebrew sephiroth (sephiroth is the plural form of sephirah), a word derived from sappir, the Hebrew for “sapphire.” Kabbalah teaches us that God did not create the world in one stroke but in stages, with the sephiroth as the means and the pattern for existence. You can see the Hebrew names for the sephiroth, with their usual translations, on the painting, but here is a list, from the top down:

1. Kether—Crown

2. Hokhmah—Wisdom

3. Binah—Understanding

4. Chesed—Mercy

5. Gevurah—Power

6. Tiferet—Beauty

7. Netzach—Eternity

8. Hod—Glory

9.Yesod—Foundation

10. Malkuth—Kingdom

Some readers may know slightly different spellings for some of the sephiroth; for example, Chokmah instead of Hokhmah. Do not let this worry you. The Hebrew alphabet is different than the Latin, and there simply is no precise rule for how to transliterate words. The very word “Kabbalah” has many variants, such as “Qabalah” and “Cabala.” Some of these have actually become associated with different branches of the tradition.

For example, Cabala is favored by Christians who have adapted the tree and its symbols to Christian concepts (for example, placing Christ in the center, at Tiferet). Qabalah, on the other hand, often refers to the non-Jewish occult tradition called Western, or Hermetic. For the sake of simplicity, I will use Kabbalah as the standard spelling throughout, and try to make clear when I am referring to the Jewish, Christian, or Western Hermetic concepts and symbolism.

According to all these traditions, the divine Creator sent the energy down in a specific pattern from Kether to Malkuth. At the same time, that pattern is not the only way we can connect the sephiroth. Because the Hebrew language has twenty-two letters, Kabbalists long ago developed the idea of twenty-two connecting lines, or pathways, between the ten sephiroth. Below we see, on the left, the pattern of Creation, and on the right, the most common version of the twenty-two pathways. This version actually belongs to the Western tradition more than the Jewish, but it’s the one most people know and, in fact, it’s the one Hermann Haindl used as the basis for his painting.

Because there are so many variations on Kabbalah—within the Jewish tradition alone the rabbis often went in different directions—we can sometimes get lost in the contradictions or, worse, take one version as absolute truth and ignore any other approaches. I have tried here to draw from all these approaches wherever useful (and within the limits of my knowledge), and at the same time attempt to put them together in a story readers can follow, hopefully without too much confusion. Hermann Haindl’s painting will help ground us by giving us a visual anchor.

The Kabbalah tree has its roots in Jewish mysticism, and inevitably we will explore the points of view of the rabbis who developed it. This does not mean that you need to be Jewish to appreciate it. As the traditions of Western and Christian Kabbalah clearly demonstrate, the tree operates very well as a symbol for many systems of belief. It really has grown into a kind of organizing principle for our human efforts to understand the world.

Because the tree is not just a narrow religious concept, we will draw on some unusual sources in our attempt to understand its message. This will include tribal and shamanic traditions, and also modern science. As well as the great rabbis we will look to contemporary Kabbalists, Tarot interpreters, and even a comic book writer who has explored the tree vividly and in great depth in his stories.

We will encounter the word “God” very often in these pages, as well as words and passages from the Bible. The tree is, after all, a Western symbol, and Western traditions are rooted in the Bible. At the same time, none of this is meant to support narrow religious ideas. Kabbalah is a mysterious journey of transformation, and one of the things it transforms is what we mean when we say “God.” I ask, therefore, that readers set aside their previous beliefs, and especially any negative experiences they may have had in their own religious upbringing. Sadly, there are far too many of these.

The symbol is a living tree. It continues to change, and adapt, and accept new ideas. While it comes from a background that is patriarchal, we do not need to accept the strict separation of male and female qualities, or the implied superiority of the masculine that sometimes seems to pervade earlier centuries of mystical thought. Instead, we can allow our own contemporary wisdom to add to the great store of teachings over the centuries.

This does not mean we reject the dedication or brilliance of earlier times. It would be worse than arrogant, it would be simple ignorance to dismiss the great achievements of such figures as the sixteenth-century Rabbi Isaac Luria, or the mysterious author of the Book of Formation two thousand years ago, or the vast synthesis created by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the late nineteenth century. But neither do we have to sweep away our own insights in a blind worship of the past.

In his Tarot deck, and now in his painting of the tree, Hermann Haindl imbues these great traditions with his devotion to the earth and his reverence for archaic goddesses and all the world’s traditions. This gives his version of the Tree of Life a slightly different character from the familiar abstract diagram. It does not change the meaning of the tree, but adds to it, helping to reinvigorate this centuries-old symbol for a new century.

ONE – The Tree and the Ladder

Think of the image of a tree. Strong, graceful, its branches reach up like long fingers into the sky. It is hundreds, maybe thousands of years old. And now think of a tree older than all, a tree whose trunk and branches connect heaven and earth, whose roots reach down into the dark mysteries below our normal consciousness, into the very origins of existence; a tree of dreams, a tree of beauty, a tree of God. A tree of life. Is our world, with all its complications, hopes, and dangers, no more than a child’s treehouse set in a vast tree that stretches through worlds upon worlds?

Now play with this image. If the tree is the connection of all life, does it begin in the dark underworld, stretch up through the existence we narrowly think of as “reality,” and reach beyond to the spiritual heaven we imagine as somewhere far above our heads? But suppose all life, all existence beg ins with the Creator. Shouldn’t the tree begin in “heaven”? And suppose our true home lies not in the world of pain and sorrow but in the divine perfection, what the legendary Welsh shaman/bard Taliesin called “the region of the summer stars.” If the tree has its roots in heaven, and its branches reach down to us, does that mean that the tree grows upside down? Maybe we are upside down—that is, confused and seeing reality the wrong way around. If we could learn to see the true way, from the point of view of the divine rather than our ordinary “common sense” view (for that which is commonly agreed on is not necessarily true), then maybe the Tree of Life would stand revealed to us. And maybe we could learn to climb the tree and return to our roots as divine creations, made in the image of the Creator but ignorant of what that really means.

People climb trees. They find their way, branch by branch, into the higher regions. Before the invention of machines of flight—balloons, gliders, airplanes—giant trees were the only way people could leave the surface of the earth. So a tree becomes a ladder, and if the tree reaches high enough it becomes a ladder to heaven itself.

Now this is a literal image, and we should not confuse ourselves and believe there actually is a tree somewhere, or a giant ladder, that climbs up into the sky (why, in fact, should heaven be literally above us, in the sky?).And we should not believe that people in ancient times were much more simple-minded than our sophisticated selves, and so believed in such concrete trees and ladders. Images are metaphors, ways to make real in our minds what we understand as intuition.

A tree that reaches into heaven, however, is a very vivid and enticing metaphor, and so has proved useful to humans the world over as a way to formulate our desire to encounter the divine. In the set of traditions known as shamanism (the word comes from a specific people in Siberia but describes practices and religious approaches found wherever humans have lived), healers and visionaries travel in trance to the spirit world. To aid their journeys they use the literal image, sometimes a pole or even a small tree, sometimes a ladder. They will set this up in the ceremony, and when they enter trance they will experience a climb up the tree or ladder into the realm of the gods, where they may find some power object or even battle the spirits for the captured soul of a sick person.

Thirty years or so of books on shamanism and trance workshops have made such visions and journeys sound almost ordinary to modern people. At the same time, those of us who grew up in mainstream Western religious traditions may assume that our own culture contains no such trance climbs up a tree or a ladder. In fact, the Bible contains several such images. Most obviously, there is the Tree of Life itself, from the Garden of Eden, and we will look closely at just what this story tells us in a moment. But there also exists an image of a ladder that reaches from heaven to earth.

In the book of Genesis, Jacob has fled his brother’s anger and is traveling in the wilderness. At night, in a place called Luz, he sets some stones for a pillow and goes to sleep. Now, stones set into a pile are themselves an image of the heavenly ascent, which is one reason why we find sacred pyramids in Egypt, Babylon, and Mexico, and why people in the Stone Age created mounds and giant hills so large they seem part of the natural landscape. Asleep, Jacob has “a vision in a dream.” He sees a ladder set on the ground, reaching up all the way to heaven. Angels—the original Hebrew word means “messengers,” for angels are messengers of the divine—ascend and descend. The power of the world above—the “kingdom of God,” as a much later prophet, Jesus of Nazareth, son of Mary, called it—moves freely between the exalted existence of the divine and the difficult world of mortals.

Notice that the angels do not just descend from their realm to ours. Instead, they move in both directions, for if you have a ladder it does not go in only one direction. This, in fact, is a basic principle of esoteric ideas in general, and the Tree of Life in particular, that existence goes in both directions, from spirit “down” into physical matter, and from matter “up” into spirit. Neither is actually superior, for a full existence depends on both of them and the interchange between them. To really understand who we are we need to recognize that we, too, contain both spirit and matter, and that these qualities actually move up and down each other. When Watson, Crick, Wilkins, and Franklin discovered the double-spiral structure of DNA, the genetic basis of life, occultists recognized this as the same image found in spiritual teachings.

We might understand this double-spiral movement a little better if we think of the creative process in humans. And here we have an excellent example in Hermann Haindl himself. Haindl is the epitome of what we could call an intuitive artist. He will often begin a work by letting paint splash on the canvas and seeing what pictures seem to emerge. We should not make the mistake, however, of thinking he acts without thought. From this instinctive response he moves to a highly conceptual work in which his life experiences, political beliefs, and sacred knowledge all combine to form a coherent whole. We might say, therefore, that an original image “descends” down the tree or ladder into physical reality on the canvas. The act of painting, and the thought that goes into it, then “ascends” into a work of art that is as intellectual as it is visual.

In the Genesis story, Jacob does not himself travel up the ladder. Unlike the shamans, he does not ascend. In a sense, there is really no need, for in the next moment, God actually appears and speaks to Jacob directly, saying that Jacob’s sons will become a great nation. When Jacob wakes up he names the place Beth-el, the “house of God,” and calls it the “gate” of heaven for, he says, “God was in this place and I did not know it. ”These ideas, especially the gate, are also part of the shamanic, and later Kabbalist, idea of the tree, or ladder, that reaches to the realm of the divine. The Tree of Life is the path by which we climb to the sacred and then return to our true selves. Wherever and whenever we perceive it we find the gate of heaven. Jacob then marks the spot with yet another prehistoric image of the link between heaven and earth, a stone pillar.

The shamans often climb the ladder or tree to struggle, even battle, the gods for the sake of helpless humans. Jacob only watches. But maybe he simply is not yet ready. Kabbalist tradition suggests that a man must not begin the study of Kabbalah until he has married and fathered children —in other words, until he has become mature and responsible. Only then can he face the powerful forces hidden within the study and practices of Kabbalah. (These traditions originated in a patriarchal culture that only rarely recognized the possibility for women to enter into them. As with so much else, the introduction of women’s points of view has radically opened new ideas and approaches to the Tree of Life and other aspects of Kabbalah.) Jacob, too, must become the master of his own life before he can go further in his knowledge of the divine.

Years after his dream vision, after he has married and begun his family, Jacob must once again confront his twin brother, with whom he has wrestled all his life, from their first moments in their mother’s womb. Once more he sleeps in the wilderness, far from human civilization, with all its safety nets of assumed reality. This, too, is a shamanic experience, to find the sacred outside everyday life. Now, instead of a vision of powers that travel up and down a ladder, Jacob encounters a single figure, a “stranger” whose face he cannot quite see. And all night the two wrestle, neither one able to defeat the other.

Tradition identifies this figure as an angel but that is not what the text actually says. When Jacob demands a blessing from the mysterious figure, the stranger gives him a new name (another common shamanic experience), Isra-el, “one who has wrestled with God.” Jacob then names the place Peni-el, the “face of God,” for he says, “I have seen God face to face and survived.” And having done this, Jacob finds the courage to go to his brother and seek peace.

As shamanic as this story is, it also is deeply Kabbalist. Though the ultimate truth of God lies beyond even the Tree of Life, the teachers identified aspects of the tree as a “greater” and “lesser face,” and one goal of the study and meditation on the ten sephiroth becomes the ability to see those divine faces—and, like Jacob, survive the experience and then go on to seek peace. Jewish Kabbalists actually identify the “lesser face” as the central sephirah, Tiferet, which they also identify with Jacob, as the image of the perfect man; Christian Kabbalists see this sephirah as Christ.

With his two visions, the ladder and the struggle, Jacob embodies the very qualities of those shamans who use poles, ladders, pillars, and living trees as vehicles to ascend to the heavenly world and claim humanity’s place among the divine. For this reason, another name for the Tree of Life, with its ten lights and twenty-two pathways, is Jacob’s ladder.

The Tree of Life diagram developed over many centuries, beginning in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and continuing to the late nineteenth century. Its origins—the roots of the tree, we might say—go back to the beginning of the Common Era (the term non-Christians use for the last two thousand years to avoid anno domini, “year of our lord”), with a remarkable work called the Sefer Yetsirah, the Book of Formation. In this very short text the anonymous writer first describes the sephiroth, the ten emanations of divine light, and the mystical power of the twenty-two Hebrew letters. The actual tree will be many centuries off, but this is where it began.

We will look at the Sefer Yetsirah more closely, but it is worth considering a religious mystical movement going on at that time in ancient Judaea for what it tells us about the origins of Kabbalah and its goals, and therefore for ways we can approach the Tree of Life, both in its diagram form and in Hermann Haindl’s remarkable painting. Two thousand y ears ago, right around the time of the teachings of Jesus, Judaism faced a great crisis. Rome was trying to crush the Jewish desire to follow its own traditions, and in the year 70, in response to Jewish rebellion, the Roman army destroyed the vast Temple of Solomon that had stood as the center of Jewish ritual and spiritual life for hundreds of years.

Without the temple, and its seasonal rituals and sacrifices, how would people join themselves to God? The Sefer Yetsirah was, in fact, one answer, and it began a strain in mystical religion called “the work of creation,” that is, the contemplation of the origins and structure of existence. Through meditation on the wonders of the sephiroth and the letters, and their place in the creation of the world, the mystic comes to a sense of the divine power that fills all existence, especially our own lives.

Another response was a kind of shamanic revival called “the work of the merkavah,” or the work of the chariot. The chariot refers to a mystic vision described in the book of Ezekiel. Ezekiel lived during the Babylonian Exile, after the destruction of the first temple (Rome actually destroyed a second temple, rebuilt after the return from Babylon). His experience was therefore meaningful to those going through the pain of Roman attacks. The prophet described a highly detailed vision he had of a heavenly chariot, wheels within wheels and winged creatures with four faces. The merkavah mystics used this vision as their own vehicle for trance journeys into the seven hekhaloth (palaces) of heaven. The purpose of these journeys was to see the divine face to face, the very experience Jacob describes after his night of wrestling.

The great detail of the merkavah writings show that the journeyers considered the hekhaloth real places and not just hallucinations or subjective images. They warn of improper responses one might make at certain points in the journey. At the same time they recognized that all this took place on an inner level, stimulated by meditation and magical practices, for they described the experience as a “descent” to the chariot, even as the traveler ascended to the palaces. The chariot was inside the self as well as in the heavenly realms.

Because the tree uses the ten sephiroth and the twenty-two pathways we naturally think of it as derived from the Sefer Yetsirah and the work of creation. And of course it is, not just because of its structure but because of its tradition of contemplating the wonders of existence. But it also derives from the work of the chariot, for the tree is a vehicle as much as a thing of wonder. We use it not just to understand how life exists, or even how to understand divine laws; we use it to understand ourselves. And we use it to move ourselves through the journey of the pathways, step by step, until we discover our own vision, as much as we are able, of divine truth. And it is the special wonder of Hermann Haindl’s painting that he shows this vehicle to be one truly of life and not just abstract thought.

When Haindl writes on his painting “der baum ist der baum ist der baum ist der baum” (“The tree is the tree is the tree is the tree,” reminiscent of Gertrude Stein’s legendary poem “A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”), he returns the philosophical concept to its literal roots. Around the world we find the Tree of Life seen as an actual tree, alive in the world. In the West we have lost our connections to nature as a divine revelation so that we tend to think of spiritual ideas as apart from the living world. We even may see the two as opposed, with anything physical being temporary and ultimately empty, while the spiritual becomes the thought that transcends nature. The Haindl tree, however, reminds us that we exist in nature, and if we cannot find the divine in living things then perhaps we will find it nowhere.

In Africa and many other places, trees with white sap have signified the Mother Goddess, for they give “milk” yet, unlike short-lived humans, they remain strong and graceful over many decades, even centuries. Ancient Egypt identified the sycamore with the goddesses Nut (of the night sky, possibly the oldest goddess), Hathor (identified with the cow goddess), and Isis, founder of civilization, bringer of Osiris back from the dead.

Osiris himself becomes embedded in a tree at one point of his story. His brother Set imprisons him in a jeweled coffin and floats him away down the Nile. The coffin drifts out to sea and lands at a place called Byblos, where a tree grows up around it to become the base of the local king’s palace. Isis finds him and removes him from the tree. Osiris’s ceremonies included the raising of a wooden pole called the Djed pillar, a symbol both of the male organ with its generative power and the human backbone, the structure that allows us to stand upright—like a tree—and move in the world. The backbone contains the life energy people in India call kundalini, sometimes thought of as a snake coiled at the base of the spine.

The image of a snake wound around a tree recalls the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden, and also the common image of healing from the Greek caduceus, two snakes wound around a stick (now a symbol of the medical profession). And, further, it may remind us of the “brazen serpent” that God tells Moses to hold before the Israelites as they travel in the wilderness. This, too, was said to heal the sick. The more we delve into the symbolism and myths of different cultures—in this case, Egypt, India, Israel, and Greece, but we could cite even more—the more we realize that myths and esoteric teachings are not fantasies or even just psychological insights, but are in fact ways to represent scientific knowledge that the modern world has largely lost.

Even in ancient Israel, people saw the Tree of Life as a real tree. Most often this was the almond, a tree whose white flowers bloomed early in spring, before its first leaves. The oil cups in sacred menorahs (candleholders) were often shaped like almond flowers. The menorahs themselves took on the form of a tree, with seven branches, one for each of the days of creation, and ultimately for each of the seven moving bodies in the sky—sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These seven bodies were the source of the seven palaces of heaven, the hekhaloth.

Long before he learned of the Kabbalah Tree of Life, Hermann Haindl witnessed a living ritual of this idea. For a number of years, he and his wife Erica were privileged to attend the annual Native American Sun Dance, in which various Indian nations come together in a great ritual of sacrifice and celebration. Young men, who have prepared themselves for an entire year, pierce their bodies and dance about a tree, offering their own blood, like sap from a tree, to strengthen what the great visionary Black Elk called the “sacred hoop” that connects all life. Interestingly, they perform the ritual around a sapling, not some ancient tree older than memory. The Tree of Life ultimately is all trees, and the youngest shoot reaches into the roots of the very beginnings of life.

To offer blood means to offer yourself, to break the barrier of skin that seems to separate you from the universe outside you. “The blood is the life,” says the Bible. The young men in the ceremony do not die or injure themselves in any permanent way. The blood sacrifice does not seek harm but a union with the natural and spiritual worlds.

Black Elk described many sacred hoops for the many peoples of the world. And yet they all form one great circle. Black Elk also spoke of a single great tree, flowering and beautiful, that shelters all the children of the earth. Similarly, the Revelation of St. John describes a Tree of Life with twelve fruits (for the twelve signs of the zodiac) that yields every month, and branches whose leaves shelter and heal all the nations of humanity.

Both these visions describe the tree’s nurturing powers, compared to the Kabbalist or shamanic vision of a kind of ladder that links heaven, earth, and the underworld. Because Hermann Haindl’s painting shows the tree so vibrantly alive, it combines both these qualities, the nurturance and the vision of the laws of creation.

The Sun Dance brings to mind two mythological tree sacrifices of great importance to European traditions. The first is Jesus on the cross, the second is the Norse/Germanic god Odin, who hangs from the world tree, Yggdrasil, to obtain the magical alphabet, the runes.

Christian teachings specifically compare the cross to the Tree of Life denied Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (we will look more closely at the Eden story in a moment). Just as some stories say that Jesus himself made the cross in his work as a carpenter, so others claim the wood literally came from the original Tree of Life. The first humans disobeyed the Creator and ate from the Tree of Knowledge, losing Paradise for all humanity. Christ gives up his own life and then returns from the dead to redeem humanity from sin. Christian myth not only links the cross to the Tree of Life, it also links Christ’s sacrifice to Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac, for Calgary, the hill where Christ died, is said to be the same place where Abraham bound Isaac and prepared to offer him to God, until an angel came and told him to sacrifice a ram instead. Jewish Kabbalah considers Isaac the embodiment of the fourth sephirah, Chesed, or mercy.

As we have seen, Christian (also Western) Kabbalah places Christ in the center of the tree, at the sixth sephirah, Tiferet. Just as we can think of the entire tree as a human body, so we also can visualize Christ at the center, suspended on the cross. (We should recognize here that the Haindl painting actually shows Christ, with his crown of thorns, on the right pillar of the tree. This is the pillar of mercy, and so a fitting place for the image of a savior. The center sephirah in the Haindl tree shows a bird. For Christians, this suggests the Holy Spirit.)

Some scholars believe that the Romans did not actually use crosses for execution but instead nailed people to simple poles (the word crucifix comes from Latin and means “fixed to a cross,” but crucifixion may not be the original term). If so, Christianity adopted the image of Christ as nailed to a cross for two reasons. First, the cross allows the human body to open up, with the arms out expansively, as if to embrace all humanity. Christ’s body becomes more like a tree, a protective shelter.

Second, the cross forms a powerful symbol of the intersection between eternity and history. In other words, the vertical line of the cross represents the divine, which is ever present, eternal, all powerful. The horizontal line signifies the historical moment and chain of events that led to Christ’s sacrifice. Another way to say this is that the vertical line symbolizes Christ’s divinity, while the horizontal line indicates Jesus’s humanity.

We find the symbolism of the cross in other traditions beside Christianity. In both ancient Greek religion and Haitian Voudoun, divinities appear at crossroads that symbolize the meeting place of different realities, especially that of gods and humans.

Though Christian Kabbalah places Christ in the center of the tree, the entire Tree of Life represents a meeting, or junction, of human history and divinity. This is because it begins with an image of eternity, in Kether, and reaches down to what we think of as “the real world” in Malkuth.

This movement goes both ways. If we think of the tree as the process of creation, then the energy moves from Kether, sephirah one, down the Tree to Malkuth, sephirah ten. But we also can think of the tree as a pathway for us to return to divine awareness. We can imagine ourselves moving up the tree, from Malkuth to Kether. And if we think of the tree as a model for our own bodies, then we can allow energy to awaken in us and rise upwards, from Malkuth at our feet to Kether at the top of our heads. Such movement can transform our ordinary view of existence, which we might call “mortal,” into an awareness of our eternal “true” selves, at one with the divine life energy that never dies.

The story of Odin’s sacrifice so recalls Christ that early myth and folklore researchers assumed the Norse writers had borrowed it from Christianity. Since then, most have agreed that the story is much older than the Christian presence in the north. It may go back to very ancient practices in Siberia of sacrificing horses (similar to the sacrifice of bulls in ancient Greece or, for that matter, rams in ancient Israel). In the myth, Odin had a horse named Ygg, and the name of the tree, Yggdrasil, may have meant “steed of Odin.”

The essence of the tree is renewal. Like serpents who shed their skin and emerge reborn—like the moon, which grows strong, then dies into darkness only to remerge once more into light—(deciduous) trees shed their leaves as the earth goes cold in winter, then returns to life in spring. According to Norse myth a great battle called Ragnarok will destroy the gods and all life. Yggdrasil itself will shatter, breaking the link between all the worlds. Only—the tree secretly contains a future man and woman, and when the old Tree of Life dies these two will stand revealed to await the renewal of creation, like a new Adam and Eve.

Odin seeks the knowledge and magical power hidden in the runes, which lie in a dark well at the base of the World Tree. To prepare himself, he wounds himself in the side and then hangs on the tree for nine days and nights. Even this is not enough, and so he gives up his right eye as an offering to Mimir, the ruler of the well. Finally, Odin reaches down from the tree and snatches up the runes. Because of Odin’s status as father of the gods, Western Kabbalah places Odin at the second sephirah, Hokhmah, identified with the “supernal father.” Hokhmah means “wisdom,” and having achieved the runes Odin became a master of true wisdom, someone who can see into all the worlds.

The runes resemble the Hebrew alphabet, for they spell words like any letters and yet they also contain special powers and symbolic meanings. We can use both alphabets for divination, and in very similar ways. The diviners would inscribe the letters on small stones or pieces of wood, put these in a bag and shake them, then reach inside for one or more letters to answer a question. In both the Futhark (runes) and the Aleph-Beth (Hebrew), every letter describes some creature or quality. For example, the third Hebrew letter, Gimel, means “camel,” while the rune Ur means “aurochs,” a European bison (extinct since the Middle Ages). Both letters, Gimel ![]() and Ur

and Ur ![]() , appear on Hermann Haindl’s painting of the High Priestess Tarot card.

, appear on Hermann Haindl’s painting of the High Priestess Tarot card.

The Sefer Yetsirah describes the Creation as the product of the ten sephiroth and the twenty-two Hebrew letters. The Kabbalah Tree of Life brilliantly combines these two in the diagram of twenty-two pathways connecting the sephiroth. Nineteenth-century Western Kabbalists then linked the letters and pathways to the twenty-two letters of the Major Arcana of the Tarot. In the Haindl tree painting we find the names of these cards on the lines between the sephiroth, while the actual Haindl Tarot cards also contain runes so that we could, in fact, use them to place the runes on the tree.

Excerpt reprinted with permission. The Kabbalah Tree: A Journey of Balance & Growth by Rachel Pollack © 2004. Llewellyn Worldwide, Ltd. PO Box 64383, St. Paul, MN 55164. All rights reserved.