Article and photos by Jeff Belanger

When in the city of Pittsburgh, a few things are unavoidable. You will see the power of Heinz ketchup, you’ll undoubtedly have a Primanti Brother’s sandwich, and all around you will be buildings, monuments, and other living testaments to Andrew Carnegie and his wealth. In December I paid a visit to the Lawrenceville branch of the Carnegie Library to see its famous headstone, get the story about the hundreds of human bodies that still lie in a mass grave in the building’s backyard, and learn about some of the ghosts that may be walking the halls of the 105-year-old building today.

When in the city of Pittsburgh, a few things are unavoidable. You will see the power of Heinz ketchup, you’ll undoubtedly have a Primanti Brother’s sandwich, and all around you will be buildings, monuments, and other living testaments to Andrew Carnegie and his wealth. In December I paid a visit to the Lawrenceville branch of the Carnegie Library to see its famous headstone, get the story about the hundreds of human bodies that still lie in a mass grave in the building’s backyard, and learn about some of the ghosts that may be walking the halls of the 105-year-old building today.

Andrew Carnegie was one of America’s earliest rags-to-riches stories. Born in Scotland in 1835, Carnegie’s father was a weaver who lost his livelihood when the Industrial Revolution introduced automated machines that made manual weaving skills obsolete. The impoverished Carnegie family immigrated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in search of a better life when Andrew was 12 years old.

Andrew Carnegie built his wealth in the steel industry, and by 1901 he was considered one of the wealthiest men in the world. The somewhat ruthless businessman became a significant philanthropist toward the end of his life and began donating millions of dollars to charity. One of his greatest achievements was funding the construction of hundreds of libraries across America. In fact, the Lawrenceville library, built in 1898, was the second library to be funded by Carnegie.

The story behind the Lawrenceville library’s ghoulish past actually begins in 1814 when Lawrenceville’s founder, William B. Foster, donated 1 ¼ acres of land to be used as a burial ground for soldiers, calling the gesture, “My free gift to the people of Lawrenceville and their children and descendants.” The land was called the Lawrenceville Burying Ground.

In 1834, the Foster family relocated from Pittsburgh, and they left the cemetery in the care of the town. The city of Lawrenceville renamed the cemetery to Washington Burial Ground, began charging for cemetery plots, and made some beautification efforts, such as walkways and fences, with the proceeds. The newly-refaced cemetery would prosper for only a very short time.

In 1868, Lawrenceville was incorporated into the rapidly-growing city of Pittsburgh, and land was becoming more of a precious commodity close to town. By this time, the cemetery wasn’t being well maintained, and the last burial would be held in 1879. So the city council of Pittsburgh, now in charge of the Washington Burial Ground, agreed to turn the land over to the Pittsburgh School Board so a school could be built… and the 450 bodies buried there would need to be moved.

The descendants of the deceased interned there were contacted and told they could come down and claim the remains of their loved ones. Of the 450 bodies, only 70 were claimed and moved to a new cemetery. The School Board promised the rest would be relocated to a small portion of the land that would be “enclosed, protected, and taken care of in a proper manner.”

Construction began on the school in 1881. “When they started building the school, as they were digging the foundation, they were finding bones,” said Melissa Gotsch, the Lawrenceville library’s manager. “They had been told it was cleared… but it wasn’t.” The workers also uncovered parts of caskets and clothes as they dug – and the locals were outraged at the atrocity. Law suits were filed, and an agreement was reached stating that all of the remaining bodies would be buried in a mass grave on the northern side of the property. Today, those 380 bodies are still there.

In 1882, the school construction was completed, and in 1898 the Lawrenceville library was built on the western side of the land. During the digging, a damaged gravestone would be unearthed and stored in the library’s basement.

In 1882, the school construction was completed, and in 1898 the Lawrenceville library was built on the western side of the land. During the digging, a damaged gravestone would be unearthed and stored in the library’s basement.

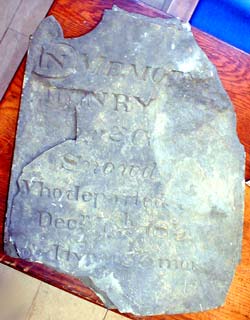

Today the gravestone is prominently displayed in the center aisle of the library next to an article from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on the mystery of whom the headstone belonged to.

Local historian Alan Becer did some research and discovered that the partially-visible engraving actually spelled out “IN MEMORY OF HENRY SNOWDEN who departed Dec. 7th 1830, aged 1 year & 3 mon.” Young Henry Snowden turned out to be one of the lucky 70 who were transferred to another cemetery.

The second floor of the library contains several empty rooms and a spooky attic with an old, rusting cast-iron bathtub in the corner. The upstairs apartment was formerly used by the library’s caretakers, but it has remained vacant for many years now. The back door of the apartment leads out to a small roof that offers a great view of north Pittsburgh. A glance down, however, offers a view of roughly ¼ acre where to your left lie the remains of approximately 380 people next to a fence and a sparse tree line. In the center of the patch of grass, a monument stands as the only remaining evidence to the bodies that still lie below.

The inscription on the monument is a testament of the compromise reached back in 1881 which reads, “Sacred to patriotism and education. This ground, one acre and a quarter, was given in 1814 by Col. William B. Foster, founder of Lawrenceville as a burial ground for our soldiers.”

The monument may hint, but unless someone told you, you wouldn’t know you were standing on hallowed ground.

The basement of the library offers a community/lecture room, and the many metal pipes that line the walls creak and groan on cold days. “This is where the tombstone was — for I don’t even know how long,” said Gotsch. “It [the headstone] just kept getting moved around down here, so in October we brought it upstairs so people could see it.

“Every now and then we hear noises down here, but we’ve never experienced anything more exciting than a radiator.”

Gotsch has worked at the Lawrenceville library since September of 2002 and has heard in the past there were janitors who were afraid to work there at night. One local ghost hunter who asked not to be identified claimed that the spirit of a child roams the hallways of the library in the evenings and has been witnessed by some of the library’s patrons.

Gotsch has worked at the Lawrenceville library since September of 2002 and has heard in the past there were janitors who were afraid to work there at night. One local ghost hunter who asked not to be identified claimed that the spirit of a child roams the hallways of the library in the evenings and has been witnessed by some of the library’s patrons.

The Lawrenceville branch of the Carnegie Library is certainly a charming building, though it hides a hundred-year-old secret. Disturbing the remains of the dead is almost a universal taboo, and when walking around the building, it’s very difficult not to think about the hundreds of bodies that lie in a mass grave just a few feet away.